library(reticulate)

py_install("package_name")Appendix A — Data Wrangling FAQ.

This is an FAQ for James Howison’s Data Wrangling course in the Information School at the University of Texas at Austin. It’s an introductory course that teaches enough python to read csv and wrangle data into mysql, then back out again to conduct some analysis.

Python packages

RStudio doesn’t have the Python packages I need

If you’re running Python in RStudio, you can install additional Python packages directly using the reticulate package.

Replace <package_name> with the name of the package you’d like to install. e.g., pandas.

Getting Data

Convert an html table to csv

http://www.convertcsv.com/html-table-to-csv.htm Careful to select the actual table you want, avoid using the “All” option in the dropdown box. Wikipedia pages sometimes have multiple tables with headers that should be columns (e.g., Season number in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_The_Simpsons_episodes_(seasons_1%E2%80%9320)#Episodes.

You could scrape and parse the HTML but that’s out of scope for this class. You could also save each converted table to a file with the season in the name (e.g., simpsons-season-1.csv) and then combine the tips below on Reading data from filenames and the glob.iglob from Read files in a directory.

Convert a table in a pdf to csv

http://tabula.technology/ or https://pdftables.com/

Read a csv file

There are several ways to read a CSV file, depending on the tool you’re using — Python, R, or Power Query. Below, we’ve included examples for each. If your CSV file doesn’t contain headers, you’ll also find steps in the examples showing how to read csv files in those case.

import pandas as pd

# With headers in the file

df = pd.read_csv('your_file.csv')

# No headers in file, supply your own in a list

headers = ["id", "year", "state_abbr", "gdp_millions"]

df = pd.read_csv('your_file.csv', names=headers, header=None)

# Display the data

print(df.head())

# No headers or uneven rows. Each row a list rather than a dict.

print(df.values.tolist()) # Converts to list of lists

# Or iterate row by row if needed

for index, row in df.iterrows():

print(row.tolist()) # Each row as a list# Using base R

data <- read.csv("your_file.csv")

# Using readr package (tidyverse)

library(readr)

data <- read_csv("your_file.csv")

# With custom delimiter

data <- read.csv("your_file.csv", sep = ",", header = TRUE)

# Without headers

data <- read.csv("your_file.csv", header = FALSE)

colnames(data) <- c("id", "year", "state_abbr", "gdp_millions")

See Reading CSV materials.

Handle files with repeated identical headers

The DictReader turns columns into keys of dicts. But we can’t have repeated keys for dicts, so you’ll end up with only one of any set of repeated columns. For example, this file has two “points” columns.

game_city,visiting_team,points,home_team,points

Austin,San Antonio,2,Austin,4As a human we can tell that one is meant to be the visiting_team_points and one is meant to be the home_team_points but only the order of the columns tells us that.

The simplest option is to edit the headers in the csv, but if you are parsing many files or files received automatically that’s not possible. You can use the same techniques as files without headers (manually declare fieldnames or use csv.reader which returns a list for each row, rather than a dictionary.)

Use a tab separated file

Tab separated files can be parsed with the same code as csv files, but with the delimiter set to “:

import pandas as pd

# Read tab separated file

df = pd.read_csv('Some_tab_separated_file.tsv', sep='\t')

# Display the data

print(df)# Using base R

data <- read.delim("Some_tab_separated_file.tsv", sep = "\t")

# Alternative with read.table

data <- read.table("Some_tab_separated_file.tsv",

sep = "\t",

header = TRUE)

# Using readr package

library(readr)

data <- read_tsv("Some_tab_separated_file.tsv")

# View the data

head(data)- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your

.tsvfile. - When the preview window opens, click the dropdown next to “Delimiter” and choose Tab.

- You should now see the columns correctly separated.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Make any adjustments (e.g., rename headers, change data types, remove columns).

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Use a fixed width file

A file that uses the number of characters to show where fields separate can be parsed using string slicing on each line.

NAME STATE TELEPHONE

John Smith WA 418-711-4111

Mary Hartford CA 319-519-4341

Evan Nolan IL 219-532-c301import pandas as pd

# Read fixed width file

# Specify column widths: name (20 chars), state (10 chars), telephone (rest)

df = pd.read_fwf('some_fixed_file.csv',

widths=[20, 10, 50],

names=['name', 'state', 'telephone'])

# Display the data

print(df)# Using read.fwf (fixed width format)

data <- read.fwf("some_fixed_file.csv",

widths = c(20, 10, -1), # -1 means read to end

col.names = c("name", "state", "telephone"),

strip.white = TRUE)

# Using readr package

library(readr)

data <- read_fwf("some_fixed_file.csv",

fwf_widths(c(20, 10, NA),

c("name", "state", "telephone")),

trim_ws = TRUE)

# View the data

head(data)- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your fixed width file.

- When the preview window opens, Power Query will try to auto-detect the format.

- Click on the dropdown next to the delimiter and select Fixed Width.

- Power Query will show vertical lines separating the columns. You can:

- Drag these lines to adjust column boundaries

- Click on the ruler to add new column separators

- Click on existing lines to remove them

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Make any adjustments (e.g., rename headers, trim spaces, change data types).

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Inserting data into the database

Drop a column from a csv en route to the database

Just choose not to insert that column by not mentioning it in the INSERT. Let’s say we want to drop the id column here:

id,name,capacity

1,AMD,700

2,Honda,2000sql_insert = """INSERT INTO my_venues( venue_name, capacity )

VALUES ( %(name)s, %(capacity)s )"""

for row in data:

# doesn't matter that row also has a key "id" because it's not

# called for in the sql_insert, ie there is no %(id)s in the

# values part.

cursor.execute(sql_insert,row)Skip a comment or preamble before the headers in my csv file

Example file:

My great dataset

Copyright 2007, big important person.

name,age,occupation

james,39,professor

heshan,36,dancerimport pandas as pd

# Skip first 2 lines (preamble) and read the rest

df = pd.read_csv('csv_with_preamble.csv', skiprows=2)

# Display the data

print(df)# Using base R - skip first 2 lines

data <- read.csv("csv_with_preamble.csv", skip = 2)

# Using readr package

library(readr)

data <- read_csv("csv_with_preamble.csv", skip = 2)

# If you need more control over which lines to skip

data <- read.csv("csv_with_preamble.csv",

skip = 2,

header = TRUE)

# View the data

head(data)- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your CSV file with preamble.

- When the preview window opens, you’ll see the preamble lines.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- In the Power Query Editor:

- Select the rows you want to remove (e.g., first 2 rows with preamble).

- Right-click and select Remove Rows → Remove Top Rows.

- Enter the number of rows to skip (e.g., 2).

- If headers are not promoted automatically:

- Click Use First Row as Headers in the Transform tab.

- Make any other adjustments needed.

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Skip a comment, or other data, in the middle of my csv file

Example file:

name,age,occupation

james,39,professor

#heshan,36,dancer

danielle,21,studentimport pandas as pd

# Read CSV and filter out rows where 'name' starts with '#'

df = pd.read_csv('csv_with_comments.csv')

df = df[~df['name'].str.startswith('#')]

# Display the data

print(df)# Using base R - read and then filter

data <- read.csv("csv_with_comments.csv")

data <- data[!startsWith(data$name, "#"), ]

# Using readr and dplyr

library(readr)

library(dplyr)

data <- read_csv("csv_with_comments.csv") %>%

filter(!startsWith(name, "#"))

# Alternative: specify comment character during read

data <- read.csv("csv_with_comments.csv",

comment.char = "#")

# View the data

head(data)- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your CSV file with comments.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- In the Power Query Editor:

- Select the column that contains the comment character (e.g., “name” column).

- Click on the dropdown arrow in the column header.

- Use Text Filters → Does Not Begin With → enter

#. - Alternatively, you can use Remove Rows → Remove Rows → Custom and filter based on conditions.

- Or use the Filter Rows option:

- Home tab → Remove Rows → Remove Alternate Rows or use custom filtering.

- Click Close & Load to bring the cleaned data into Excel.

Handle files with multiple data sections

Some CSV files have multiple data sections, each with a little header. Read these as plain text files and then parse each “minicsv” to treat that section as a file.

For example The US DOJ Universal Crime Reporting Stats does this. If you select more than one state you get data like (with some headers/footers removed):

Estimated crime in Alabama

Year,Population,Violent crime total

2010,4785401,18363

2011,4803689,20166

2012,4822023,21693

Estimated crime in Alaska

Year,Population,Violent crime total

2010,714146,4537

2011,723860,4416

2012,731449,4412

Estimated crime in Arizona

Year,Population,Violent crime total

2010,6413158,26528

2011,6467315,26789

2012,6553255,28108Each state’s data is repeated in a separate little csv embedded in the larger file.

Eventually we want to create a state column to go along with the others:

State,Year,Population,Violent crime totalTo do this we can split up the file and then read each of as though they were separate CSVs. After the split this ends up very similar to the approach we’d use if these were separate files in a directory.

import pandas as pd

import re

from io import StringIO

# Read the entire file as text

with open("CrimeStatebyState.csv") as file:

lines = file.readlines()

# Initialize list to store all dataframes

all_data = []

current_section = []

state = ""

# Process line by line

for line in lines:

if line.startswith("Estimated"):

# Save previous section if exists

if current_section and state:

# Convert section to dataframe with chaining

section_text = ''.join(current_section)

df_section = (pd.read_csv(StringIO(section_text))

.assign(State=state))

all_data.append(df_section)

# Extract new state name

match = re.search('Estimated crime in (.*)$', line)

state = match.group(1).strip()

current_section = []

elif line.strip(): # Skip empty lines

current_section.append(line)

# Process the last section

if current_section and state:

section_text = ''.join(current_section)

df_section = (pd.read_csv(StringIO(section_text))

.assign(State=state))

all_data.append(df_section)

# Combine all sections into one dataframe

df_final = pd.concat(all_data, ignore_index=True)

# Display the data

print(df_final)library(tidyverse)

# Read the entire file as text

lines <- readLines("CrimeStatebyState.csv")

# Initialize variables

state <- ""

all_data <- tibble()

# Process line by line

current_section <- c()

for (line in lines) {

if (str_detect(line, "^Estimated crime in")) {

# Save previous section if exists

if (length(current_section) > 0 && state != "") {

# Parse the mini-csv

temp_data <- read_csv(paste(current_section, collapse = "\n"),

show_col_types = FALSE)

temp_data <- temp_data %>% mutate(State = state)

all_data <- bind_rows(all_data, temp_data)

}

# Extract new state name

state <- str_extract(line, "(?<=Estimated crime in ).*")

current_section <- c()

} else if (line != "") {

# Add line to current section

current_section <- c(current_section, line)

}

}

# Process the last section

if (length(current_section) > 0 && state != "") {

temp_data <- read_csv(paste(current_section, collapse = "\n"),

show_col_types = FALSE)

temp_data <- temp_data %>% mutate(State = state)

all_data <- bind_rows(all_data, temp_data)

}

# View the result

head(all_data)Power Query doesn’t have a built-in way to handle multiple embedded CSV sections automatically. You’ll need to manually process the file:

Option 1: Pre-process the file

- Before loading into Power Query, use Python or R to split the file into separate CSVs or restructure it into a single table with a State column.

Option 2: Manual transformation in Power Query

- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Use Split Column → By Delimiter or custom M code to identify section headers.

- This approach requires custom M code and can be complex. Example pattern:

- Load as text (not CSV)

- Identify rows with “Estimated crime in”

- Fill down the state name

- Remove section header rows

- Parse remaining rows as CSV

Recommended: Pre-process with Python/R script before loading into Power Query for easier handling.

which outputs:

{'Alabama': 'Year,Population,Violent crime total\n'

'2010,4785401,18363\n'

'2011,4803689,20166\n'

'2012,4822023,21693\n',

'Alaska': 'Year,Population,Violent crime total\n'

'2010,714146,4537\n'

'2011,723860,4416\n'

'2012,731449,4412\n',

'Arizona': 'Year,Population,Violent crime total\n'

'2010,6413158,26528\n'

'2011,6467315,26789\n'

'2012,6553255,28108\n'}Now we’ve built up a dictionary where the keys are state names and the values are the mini-csvs (each as a single long string). Now we can use our familiar csv parsing code to parse each “mini” csv.

Only wrinkle is that our csv is in a string rather than a file but python has a way to treat a string as a file. io.StringIO(somestring) can be used in place of a file.

import pandas as pd

from io import StringIO

# Read and combine all mini-CSVs with chaining

final_df = (pd.concat([

pd.read_csv(StringIO(state_csv)).assign(State=state)

for state, state_csv in dict_by_state.items()

], ignore_index=True))

print(final_df)library(tidyverse)

# Assuming dict_by_state is a named list with state names as names

# and CSV strings as values

# Read and combine all mini-CSVs with state information

all_data <- map2_dfr(names(dict_by_state), dict_by_state, function(state, state_csv) {

read_csv(state_csv) %>%

mutate(State = state)

})

# Display the data

print(all_data)Handle multiple headers in columns or cells merged across columns

If your Excel sheet has multiple rows of headers formed by merged cells, save as a csv which will look something like this. You don’t need to unmerge the headers in Excel, just export a csv.

,Agriculture,,,,Industry,,,,Services,,,

,Male,,Female,,Male,,Female,,Male,,Female,

,1990-92,2011-14,1990-92,2011-14,1990-92,2011-14,1990-92,2011-14,1990-92,2011-14,1990-92,2011-14

Afghanistan,..,..,..,..,..,..,..,..,..,..,..,..See long explanation at Handling Multi Index CSVs.

Handle missing values in rows or cells merged across rows, usually first column

Reuse a value from the last row by not resetting a variable. Some CSV formatted for reading carry values down, usually resulting from vertically merged cells in the first columns (or rowspan in html). e.g.:

rank,country,year,olympic_gold

1,Russia,1980,43

2,Australia,1980,3

,Bahamas,1980,3

4,Thailand,1980,1See how Bahamas is missing a rank? That’s because the 2 in the line above was applied to both of them with a merged and vertically centered cell. But when you save as csv that goes away and only one row has the value. Thankfully it’s the top row, so we can let the value “fall through”. All we need to do is pull it out of the row into a variable and not reset that variable if row["rank"] is blank.

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('olympic_data.csv').assign(rank=lambda d: d['rank'].ffill())

print(df)library(tidyverse)

# Read CSV file

df <- read_csv('olympic_data.csv')

# Forward fill missing values in 'rank' column

df <- df %>%

fill(rank, .direction = "down")

# Display the data

print(df)- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your CSV file with merged cells.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Select the column with missing values (e.g., “rank” column).

- Go to Transform tab → Fill → Down.

- This will copy the last non-blank value down to fill the blanks.

- Make any other adjustments needed.

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Handle multiple values inside a cell

Use str.split() to pull them into a list. This happens when a field is actually a list but the user didn’t want to break up the data into relational tables.

student,committee

James,Kevin;Bob;Carsten;Donimport pandas as pd

# Read CSV file

df = pd.read_csv('student_committee.csv')

# Split the committee column and explode into separate rows

df = df.assign(committee=df['committee'].str.split(';')).explode('committee')

# Display the data

print(df)library(tidyverse)

# Read CSV file

df <- read_csv('student_committee.csv')

# Split the committee column and separate into rows

df <- df %>%

separate_rows(committee, sep = ";")

# Display the data

print(df)- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your CSV file.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Select the column with multiple values (e.g., “committee” column).

- Go to Transform tab → Split Column → By Delimiter.

- Choose the delimiter (e.g., semicolon

;). - Select Split into Rows (not columns).

- Click OK.

- Each value will now be in a separate row with the same student name.

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Split a complex field into multiple columns

Use regex to get the separate parts. Regex practice here: https://regexone.com/ and all the documentation you could ever want here: http://www.regular-expressions.info/

import pandas as pd

# Extract season and episode numbers from show_code

df = (

pd.read_csv('shows.csv') # Step 1: Read CSV file into a DataFrame

.join( # Step 2: Join extracted columns directly

lambda df_: df_['show_code']

.str.extract(r'[sS](\d+)[eE](\d+)') # Step 3: Extract season & episode numbers

.set_axis(['season', 'episode'], axis=1) # Step 4: Rename the extracted columns

)

)

# Step 5: Display the resulting DataFrame

print(df)library(tidyverse)

# Read CSV file

df <- read_csv('shows.csv')

# Extract season and episode from show_code using regex

df <- df %>%

extract(show_code,

into = c("season", "episode"),

regex = "s(\\d+)e(\\d+)",

remove = FALSE)

# Display the data

print(df)- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your CSV file.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Select the column with the complex field (e.g., “show_code” column).

- Go to Transform tab → Extract → Text Between Delimiters.

- For season: Extract text after “s” and before “e”

- For episode: Extract text after “e”

- Or use Split Column → By Delimiter:

- First split by “s” to isolate the season-episode part

- Then split by “e” to separate season and episode

- Rename the new columns to “season” and “episode”.

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Get a zip code out of an address field

business,address,phone

Daisy Chain,"22344 Newfound Road, Austin, 78722, USA",512 345 4456Use a regex looking for five digits. Can backfire if house number is also five digits so use re.findall() and take last item since zip is at end of address.

import pandas as pd

import re

# Cleanly extract ZIP codes using method chaining

df = (

pd.read_csv('businesses.csv') # Step 1: Read CSV file into a DataFrame

.assign( # Step 2: Add or modify columns using .assign()

zip_code=lambda df_: ( # Create a new column 'zip_code'

df_['address']

.str.findall(r'\d{5}') # Step 3: Find all 5-digit numbers in the address (ZIP-like patterns)

.str[-1] # Step 4: Take the last match from the list (likely the actual ZIP code)

)

)

)

# Step 5: Display the cleaned DataFrame with the new zip_code column

print(df)library(tidyverse)

# Read CSV file

df <- read_csv('businesses.csv')

# Extract zip code (last 5 digits in address)

df <- df %>%

mutate(zip_code = str_extract_all(address, "\\d{5}") %>%

map_chr(~tail(.x, 1)))

# Display the data

print(df)- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your CSV file.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Select the “address” column.

- Go to Add Column tab → Custom Column.

- Enter a formula to extract the last 5-digit number:

- Name:

zip_code - Formula: Use M code with Text functions to find the last 5 consecutive digits

- Name:

- Or manually:

- Transform tab → Extract → Last Characters (if zip is always at the end)

- Then clean up to get only the 5 digits

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Note: For complex patterns, consider pre-processing with Python/R before loading into Power Query.

Remove dollar signs and commas from field

Use re.sub or str.replace. Removing them is the same as replacing them with an empty string "". Only trick is remembering that in a regex a literal $ is obtained with \$. You can make a group of characters to match with square brackets and match both the $ sign and any commas. The regex can match anywhere in the string so it can replace all the commas etc.

import pandas as pd

df = (

pd.read_csv('financial_data.csv')

.assign(

money=lambda df_: (

df_['money']

.str.replace(r'[\$,]', '', regex=True)

.pipe(pd.to_numeric, errors='coerce')

)

)

)

print(df)library(tidyverse)

# Read CSV file

df <- read_csv('financial_data.csv')

# Remove dollar signs and commas from money column

df <- df %>%

mutate(money = str_remove_all(money, "[$,]"),

money = as.numeric(money))

# Display the data

print(df)-- Using REPLACE function (works in most databases)

SELECT

REPLACE(REPLACE(money, '$', ''), ',', '') AS cleaned_money

FROM financial_data;

-- Convert to numeric after cleaning

SELECT

CAST(REPLACE(REPLACE(money, '$', ''), ',', '') AS DECIMAL(10,2)) AS money_numeric

FROM financial_data;

-- Update existing column

UPDATE financial_data

SET money = REPLACE(REPLACE(money, '$', ''), ',', '');

-- PostgreSQL: Using REGEXP_REPLACE

SELECT

REGEXP_REPLACE(money, '[\$,]', '', 'g') AS cleaned_money

FROM financial_data;- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your CSV file.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Select the column with dollar signs and commas (e.g., “money” column).

- Go to Transform tab → Replace Values.

- In the dialog:

- Value To Find:

$ - Replace With: (leave empty)

- Click OK

- Value To Find:

- Repeat the process for commas:

- Transform tab → Replace Values

- Value To Find:

, - Replace With: (leave empty)

- Click OK

- Change the data type to number:

- Click on the column header icon (ABC/123)

- Select Decimal Number or Whole Number

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Format a field using commas or dollar signs

Can do this either in your database query or in Python/R.

import pandas as pd

# Format numeric values in 'money' column with dollar signs and commas

df = (

pd.read_csv('financial_data.csv') # Read CSV file into a DataFrame

.assign( # Add a new formatted column

display_money=lambda df_: (

df_['money']

.apply(lambda x: f"${x:,.2f}") # Format each number as $#,###.##

)

)

)

# Display the formatted DataFrame

print(df)See https://pyformat.info for more info, although it’s missing the comma thing which is documented here: https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0378/

library(tidyverse)

library(scales)

# Read CSV file

df <- read_csv('financial_data.csv')

# Format money column with dollar signs and commas

df <- df %>%

mutate(display_money = dollar(money))

# Display the data

print(df)-- FORMAT adds commas and two decimal places, adding .00

-- or truncating to two decimal places.

SELECT FORMAT(your_table.money,2)

FROM your_table

-- Now add a $ in front

SELECT CONCAT('$', FORMAT(your_table.money,2)) as display_money

FROM your_table- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your CSV file.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Select the money column.

- Change the data type to Currency or Decimal Number:

- Click on the column header icon (ABC/123)

- Select Currency for automatic dollar sign and comma formatting

- Or select Decimal Number for just comma formatting

- For custom formatting:

- Add Column tab → Custom Column

- Formula:

"$" & Text.From([money], "en-US")

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

- In Excel, you can further format the column:

- Right-click column → Format Cells

- Choose Currency or Accounting format

- Set decimal places to 2

Handle different date formats on the way into the database

Create a python datetime object, pass to parameterized queries. If column is DATE rather than DATETIME time portion will be dropped on insert.

import pandas as pd

from datetime import datetime

# Convert 'start_time' strings to datetime objects

df = (

pd.read_csv('events.csv') # Read CSV file into a DataFrame

.assign( # Modify or add columns within the same chain

start_time=lambda df_: ( # Create or replace the 'start_time' column

pd.to_datetime(df_['start_time']) # Convert string to datetime objects

)

)

)

# Display the final DataFrame

print(df)Parsing dates with specific formats:

import pandas as pd

# If dates are in a specific format (e.g., "03/30/2013 14:30")

df = (

pd.read_csv('events.csv')

.assign(start_time=lambda d: pd.to_datetime(d['start_time'], format='%m/%d/%Y %H:%M'))

)Handling multiple date formats in the same column:

import pandas as pd, dateutil.parser

df = (

pd.read_csv('events.csv')

.assign(start_time=lambda d: d['start_time'].apply(dateutil.parser.parse))

)Detecting ambiguous dates:

from dateutil import parser

def parse_date(string):

try:

# Check if date is ambiguous

if (parser.parse(string) == parser.parse(string, yearfirst=True) ==

parser.parse(string, dayfirst=True)):

return parser.parse(string)

else:

print(f"Ambiguous date: {string}")

return None

except:

return None

df = (

pd.read_csv('events.csv')

.assign(start_time=lambda d: d['start_time'].apply(parse_date))

)library(tidyverse)

library(lubridate)

# Read CSV file

df <- read_csv('events.csv')

# Convert string dates to datetime objects

df <- df %>%

mutate(start_time = ymd_hms(start_time))

# Display the data

print(df)Parsing dates with specific formats:

# For format "03/30/2013 14:30"

df <- df %>%

mutate(start_time = mdy_hm(start_time))

# For format "2013-03-30"

df <- df %>%

mutate(start_time = ymd(start_time))Handling multiple date formats:

# Parse mixed formats (lubridate tries to guess)

df <- df %>%

mutate(start_time = parse_date_time(start_time,

orders = c("mdy HM", "ymd", "dmy")))Common date parsing functions in lubridate: - ymd() - Year, Month, Day (2013-03-30) - mdy() - Month, Day, Year (03/30/2013) - dmy() - Day, Month, Year (30/03/2013) - ymd_hms() - Year, Month, Day, Hour, Minute, Second

- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your CSV file.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Select the date column.

- Power Query will attempt to auto-detect the date format.

- If not detected correctly:

- Click on the column header icon (ABC/123)

- Select Date or Date/Time

- For custom date formats:

- Transform tab → Data Type → Using Locale

- Select the appropriate locale that matches your date format

- Example: “English (United States)” for MM/DD/YYYY format

- Or use Add Column → Custom Column with Date functions:

Date.FromText([date_column], "en-US")for US formatDate.FromText([date_column], "en-GB")for UK format

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Note: Power Query is generally good at detecting date formats automatically. If you have mixed formats in the same column, consider cleaning the data first or using error handling in custom columns.

Record the time I created a record

For SQL use NOW(), for Python use datetime.datetime.now(), for R use Sys.time().

import pandas as pd

from datetime import datetime

df = (

pd.read_csv('events.csv')

.assign(log_time=lambda _: datetime.now()) # Add a new column with the current timestamp

)

# Display the data

print(df)library(tidyverse)

library(lubridate)

# Read CSV file

df <- read_csv('log_data.csv')

# Add timestamp column with current time

df <- df %>%

mutate(log_time = now())

# Display the data

print(df)-- Insert with current timestamp

INSERT INTO log_data(message, log_time)

VALUES ('some message', NOW());

-- Using parameterized query (syntax varies by database)

INSERT INTO log_data(message, log_time)

VALUES (?, NOW());

-- PostgreSQL

INSERT INTO log_data(message, log_time)

VALUES ($1, NOW());

-- Create table with automatic timestamp

CREATE TABLE log_data (

id SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

message TEXT,

log_time TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW()

);

-- Then insert without specifying log_time

INSERT INTO log_data(message)

VALUES ('some message');

-- Update with current timestamp

UPDATE log_data

SET log_time = NOW()

WHERE id = 1;- Power Query doesn’t directly support “current timestamp” during data import.

- However, you can add a timestamp column:

- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Click Transform Data to open the Power Query Editor.

- Go to Add Column tab → Custom Column.

- Enter:

- Column Name:

log_time - Formula:

DateTime.LocalNow()

- Column Name:

- Click OK.

- The timestamp will be set when the query refreshes.

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Note: In Power Query, the timestamp is set when the query runs/refreshes, not when individual rows are created.

Alternative - Add timestamp in Excel: * After loading data to Excel * Add a formula in a new column: =NOW() or =TODAY() * Copy and paste as values to preserve the timestamp

Get data from filenames

Use a regex to pull a field from the filename in a variable. Useful to combine with reading many csvs of same format (glob.iglob).

import pandas as pd

import re

# Example filename

filename = "2008data.csv"

# Extract year from filename using regex

match = re.search(r'(\d+)data\.csv', filename)

year = match.group(1)

# Read CSV file

df = pd.read_csv(filename)

# Add year column from filename

df['year'] = year

# Display the data

print(df)Reading multiple files with data from filenames:

import glob

# Read all CSV files matching pattern

all_data = []

for filename in glob.glob('*data.csv'):

# Extract year from filename

match = re.search(r'(\d+)data\.csv', filename)

if match:

year = match.group(1)

# Read and add year column

df = pd.read_csv(filename)

df['year'] = year

all_data.append(df)

# Combine all dataframes

final_df = pd.concat(all_data, ignore_index=True)

print(final_df)library(tidyverse)

# Example filename

filename <- "2008data.csv"

# Extract year from filename using regex

year <- str_extract(filename, "\\d+")

# Read CSV file

df <- read_csv(filename)

# Add year column from filename

df <- df %>%

mutate(year = year)

# Display the data

print(df)Reading multiple files with data from filenames:

library(fs)

# Get all CSV files matching pattern

files <- dir_ls(glob = "*data.csv")

# Read all files and extract year from filename

all_data <- map_dfr(files, function(file) {

year <- str_extract(file, "\\d+")

read_csv(file) %>%

mutate(year = year)

})

# Display the data

print(all_data)- Power Query can extract data from filenames when loading multiple files from a folder.

- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Folder.

- Browse and select the folder containing your CSV files.

- Click Combine → Combine & Transform Data.

- In the Power Query Editor, you’ll see a column called Source.Name with filenames.

- Extract data from filename:

- Select the Source.Name column

- Add Column tab → Extract → Text Before Delimiter

- Or use Add Column → Custom Column

- Formula example to extract year:

Text.Middle([Source.Name], 0, 4)(if year is first 4 characters)

- For regex-like extraction:

- Add Column → Custom Column

- Use Text functions to parse the filename

- Example: Extract numbers from “2008data.csv”

- Rename the extracted column to “year”.

- Remove the Source.Name column if not needed.

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Process lots of csv with the same format

Use Path.glob which returns a list of files that you can iterate over. Very useful to combine with getting data from filenames (see above). (Older code uses glob.iglob for same effect.)

import pandas as pd

from pathlib import Path

# Read all CSV files in a directory

all_data = []

for filename in Path('dir_of_files').glob('*.csv'):

df = pd.read_csv(filename)

all_data.append(df)

# Combine all dataframes

final_df = pd.concat(all_data, ignore_index=True)

# Display the data

print(final_df)Alternative with list comprehension:

# More concise approach

all_data = [pd.read_csv(f) for f in Path('dir_of_files').glob('*.csv')]

final_df = pd.concat(all_data, ignore_index=True)

print(final_df)library(tidyverse)

library(fs)

# Read all CSV files in a directory

all_data <- dir_ls("dir_of_files", glob = "*.csv") %>%

map_dfr(read_csv)

# Display the data

print(all_data)Alternative approach:

# Get list of files

files <- list.files("dir_of_files", pattern = "\\.csv$", full.names = TRUE)

# Read and combine all files

all_data <- map_dfr(files, read_csv)

# Display the data

print(all_data)- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Folder.

- Browse and select the folder containing your CSV files.

- Power Query will show a list of all files in the folder.

- Click Combine → Combine & Transform Data.

- In the dialog:

- Select the sample file to use as a template

- Power Query will automatically apply the same transformation to all CSV files

- Click OK.

- Power Query will load and combine all CSV files with the same structure.

- The combined data will appear in the Power Query Editor.

- Make any additional transformations needed.

- Click Close & Load to bring all the combined data into Excel.

Note: All CSV files should have the same structure (same columns) for automatic combining to work properly.

Combining filename reading and processing a directory

Extract data from filenames while processing multiple CSV files in a directory.

import pandas as pd

from pathlib import Path

# Read all CSV files and extract state from filename

all_data = []

for filename in Path('dir_of_files').glob('*.csv'):

# Extract state name from filename (without extension)

state = Path(filename).stem

# Read CSV file

df = pd.read_csv(filename)

# Add state column from filename

df['state'] = state

all_data.append(df)

# Combine all dataframes

final_df = pd.concat(all_data, ignore_index=True)

# Display the data

print(final_df)library(tidyverse)

library(fs)

# Read all CSV files and extract state from filename

all_data <- dir_ls("dir_of_files", glob = "*.csv") %>%

map_dfr(function(file) {

# Extract state name from filename (without extension)

state <- path_ext_remove(path_file(file))

# Read CSV and add state column

read_csv(file) %>%

mutate(state = state)

})

# Display the data

print(all_data)Alternative approach:

# Get list of files

files <- list.files("dir_of_files", pattern = "\\.csv$", full.names = TRUE)

# Read and combine with state from filename

all_data <- map_dfr(files, function(file) {

state <- tools::file_path_sans_ext(basename(file))

read_csv(file) %>%

mutate(state = state)

})

print(all_data)- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Folder.

- Browse and select the folder “dir_of_files” containing your CSV files.

- Click Combine → Combine & Transform Data.

- In the Power Query Editor, you’ll see a column called Source.Name with filenames.

- Extract state from filename:

- The Source.Name column contains the full filename (e.g., “texas.csv”)

- Add Column tab → Custom Column

- Name:

state - Formula:

Text.BeforeDelimiter([Source.Name], ".") - This extracts the filename without the extension

- Or use the Extract feature:

- Select Source.Name column

- Transform tab → Extract → Text Before Delimiter

- Enter

.as the delimiter

- Remove the Source.Name column if not needed.

- Click Close & Load to bring all the combined data into Excel.

Handle files that cause a UnicodeEncodeError character encoding issues

Three things to get to match up: 1) the collation of the database, 2) the encoding used by Python/R to open the file, and 3) the charset of the database connection.

Often the best approach is to open the CSV file in your text editor and save it as UTF-8, then set everything to handle UTF-8.

import pandas as pd

# Read CSV file with UTF-8 encoding

df = pd.read_csv('tricky_file.csv', encoding='utf-8')

# Display the data

print(df)Handling encoding errors:

# If you encounter encoding errors, try different encodings

# Common encodings: 'utf-8', 'latin-1', 'iso-8859-1', 'cp1252'

# Option 1: Try latin-1 encoding

df = pd.read_csv('tricky_file.csv', encoding='latin-1')

# Option 2: Ignore errors

df = pd.read_csv('tricky_file.csv', encoding='utf-8', errors='ignore')

# Option 3: Replace errors with a placeholder

df = pd.read_csv('tricky_file.csv', encoding='utf-8', errors='replace')

# Option 4: Use surrogateescape (for advanced use)

with open('tricky_file.csv', encoding='utf-8', errors='surrogateescape') as f:

df = pd.read_csv(f)For database connections:

import pymysql

# Set charset when creating database connection

connection = pymysql.connect(

host="localhost",

user="username",

password="password",

database="dbname",

charset="utf8mb4" # Use utf8mb4 for full Unicode support

)See also: - Python text file processing: http://python-notes.curiousefficiency.org/en/latest/python3/text_file_processing.html

library(tidyverse)

# Read CSV file with UTF-8 encoding

df <- read_csv('tricky_file.csv', locale = locale(encoding = "UTF-8"))

# Display the data

print(df)Handling encoding errors:

# Try different encodings if UTF-8 doesn't work

# Common encodings: "UTF-8", "latin1", "ISO-8859-1", "Windows-1252"

# Option 1: Try latin1 encoding

df <- read_csv('tricky_file.csv', locale = locale(encoding = "latin1"))

# Option 2: Using base R with encoding

df <- read.csv('tricky_file.csv', fileEncoding = "UTF-8")

# Option 3: Detect encoding automatically

library(readr)

guess_encoding('tricky_file.csv')

# Then use the detected encoding

df <- read_csv('tricky_file.csv', locale = locale(encoding = "detected_encoding"))For database connections:

library(DBI)

library(RMySQL)

# Set charset when creating database connection

con <- dbConnect(

RMySQL::MySQL(),

host = "localhost",

user = "username",

password = "password",

dbname = "dbname",

encoding = "utf8"

)- Power Query usually auto-detects file encoding, but you can specify it manually.

- Open Excel → Data tab → Get Data → From File → From Text/CSV.

- Browse and select your CSV file.

- In the import dialog, click on the File Origin dropdown.

- Select the appropriate encoding:

- 65001: Unicode (UTF-8) - Most common for international characters

- 1252: Western European (Windows) - Common for Western languages

- 28591: Western European (ISO) - ISO-8859-1/Latin-1

- If characters still appear incorrectly:

- Try different encoding options from the dropdown

- Or save the file as UTF-8 in a text editor first

- Click Transform Data to continue with transformations.

- Click Close & Load to bring the data into Excel.

Note: If you’re having persistent encoding issues, the best approach is to: 1. Open the file in a text editor (like Notepad++, VSCode, or Sublime Text) 2. Save it with UTF-8 encoding 3. Then reload it in Power Query

See also: MySQL collations: http://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/5.0/en/charset-unicode-sets.html

Handle data for multiple years or periods

Sometimes data is gathered for multi-year periods, such as a measurement for sports audience with a year value of 2003-2005. We often face the challenge of comparing this data with data collected for single years, or compare to other periods, such as 2004-2006. Notice that I’m calling this a Period rather than a year. We want to do comparisons per year, so we have to map between Period and Year, and make some estimates.

First we create a Period entity with a name: 2003-2005 becomes Period(id, name) with a row of (1,2003-2005). Then we can map that Period to Year. One way would be to have an attribute for Period of start_year and end_year. Another option might be easier for querying and grouping would be to say Period habtm Year.

Then we have to decide how the data was collected. Two options are common: either it’s a total for that period (how many people attended any game within the period?) or it’s an average for the years in the period (the value represents the yearly attendance over this period).

That suggests a third modeling option: Audience has_many PeriodMeasure. PeriodMeasure has_many Year through YearlyEstimate. Where PeriodMeasure has (id,name,type,value) where type is either “average” or “annual”. YearlyEstimate has (id,period_measure_id,year_id,estimate).

Database queries

My query using OR is returning unexpected rows

In SQL AND has precedence over OR which can lead to strange results. If you are specifying alternative values for one filter it’s simpler to use IN. Rather than

WHERE year = 2004 OR year = 2008 OR year = 2009(which will work but is not preferred) say

WHERE year IN (2004,2008,2009)In addition to being shorter and clearer it is also safer if you have other conditions in your WHERE clause. You might try:

WHERE name = "james" AND year = 2004 OR year = 2006But that will not get records for James from 2004 or 2006. It will get all records from 2006 and just the James records from 2004. That is because AND is resolved before OR. What the server sees is:

WHERE ( name = "james" AND year = 2004 ) OR year = 2006when you meant (and these parens change the order):

WHERE name = "james" AND ( year = 2004 OR year = 2006 )So just say:

WHERE name = "james" AND year IN (2004,2006)This is particularly problematic if you have a join in the WHERE clause because it can create false records.

SELECT *

FROM observations, species

WHERE observations.species_id = species.id AND

year = 2004 OR year = 2008 OR year = 2009But that will give unexpected results because the AND pulls the first year to it and leaves the other years on their own. You can see this with parens (this is what the query above actually does):

SELECT *

FROM observations, species

WHERE (

observations.species_id = species.id

AND year = 2004

)

OR

year = 2008

OR

year = 2009This includes rows that never existed (because they are generated by the cross-join in the FROM clause but not eliminated by the join condition in the WHERE). What you want would require parens around the OR clause to force it to be resolved first.

SELECT *

FROM observations, species

WHERE observations.species_id = species.id

AND

( year = 2004 OR year = 2008 OR year = 2009 )But it’s simpler and safer to say:

SELECT *

FROM observations, species

WHERE observations.species_id = species.id

AND year IN (2004,2008,2009)Understand three forms of COUNT

The three forms of COUNT are: 1. COUNT(*) counts the number of rows (in a table or in a group). 2. COUNT(DISTINCT column) counts the unique values in a column. 3. COUNT(column) counts the number of non-NULL values in a column.

I often advise people to avoid COUNT(column) because I find the semantics confusing in a query. I mean that what people are intending to get is unclear. More, though, I haven’t come across a time when it is necessary.

Whenever you are tempted to use COUNT(column), especially when using GROUP BY ask yourself whether COUNT(*) is clearer and what you actually mean. Usually when we are grouping we are asking “How many somethings have this value” (e.g., How can performances does a band do? or How many tickets did each person buy?). These are questions about the number of rows, not the number of non-NULL values.

ps. I’m very interested to find an example where COUNT(column) is the ideal thing, so please email me if you see one. Only thing I can think of is something like counting records with relationships. e.g. a table like people(id,name,sig_other)

--How many people have sig others?

SELECT COUNT(sig_other)

FROM peopleBut I think that would be much clearer as:

SELECT COUNT(*) as sig_other_count

FROM people

WHERE sig_other IS NOT NULLSee: http://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/5.7/en/group-by-functions.html#function_count and http://www.w3schools.com/sql/sql_func_count.asp

Query a period from a list of start dates

Sometimes we want to match an event up with a period in which it happened. For example, we want to say what phase of the moon a crime occurred in. For the crimes we have a specific date, but for the moon phases we might only have the start date. e.g,

start_datetime,phase

2017-01-05 04:20:00,First Quarter

2017-01-12 01:30:00,Full Moon

2017-01-19 02:51:00,Last Quarter

2017-01-27 10:47:00,New Moon

2017-02-03 12:03:00,First QuarterHow could we query this table to find the phase of the moon for the date 2017-01-22? Looking above we, as humans, can say that it falls between the third and fourth rows, so we can conclude that the moon was in the “Last Quarter” on the 22nd. But how would we do this in sql?

If we had both the start and end dates we could write this as:

SELECT phase

FROM moon_phases

WHERE `2017-01-22` BETWEEN start_datetime AND end_datetimebut we don’t have the end_datetime. Or rather we have the end_datetime but only by reading the table in order. Remember that SQL queries examine each row, returning a TRUE or FALSE value. So we can’t ask queries that are “across rows” meaning we can’t use the start_date of the “next” row as the end_date of the previous row.

We can, though, reframe the question: Can we find the last phase that started before our date of interest?

SELECT phase

FROM moon_phases

WHERE start_datetime < "2017-01-22"

ORDER BY start_datetime DESC -- newest at top

LIMIT 1Ah, that works.

However that works for individual dates, but it doesn’t lend itself to joins, or for finding the relevant phase for a list of crimes. We could use python to execute this query once for each row in the database, using a parameterized query for each row and storing the result in a “moon_phase” column in the crimes table.

But we can use it in a correlated sub-query, which executes once for each row (unlike a simple sub-query that executes only once).

SELECT *

FROM crimes

JOIN moon_phases

ON moon_phases.id = (

SELECT moon_phases.id

FROM moon_phases

WHERE moon_phases.start_datetime <= crimes.crime_datetime

ORDER BY moon_phases.start_datetime DESC

LIMIT 1 )Another possible approach is to add an end_date column to the table. Alter the table to add a new column end_date.

ALTER TABLE moon_phases

ADD end_datetime DATE;If the periods have a regular length (e.g., 30 days) this can be much simpler (one could also use DATE_ADD and INTERVAL in a SELECT query directly.)

UPDATE moon_phases

SET end_datetime = DATE_ADD(start_datetime, INTERVAL 30 DAY)However moon phases aren’t regular in duration (and the general case of periods from an ordered list of dates is interesting):

We can set the end_datetime using python code. First we get the ids of all the periods in order:

sql = """SELECT start_date

FROM moon_phases

ORDER BY start_date ASC"""

cursor.execute(sql)

results = cursor.fetchall() # list of dicts

# make into a simple list of datetimes

just_datetimes = []

for row in results:

just_datetimes.append(row['start_datetime'])Now we can offset this list to find the end_dates. We make two lists, the first one is all start_dates, so it is missing the last item. The second list is all end_dates, so it is missing the first item. Then we use the zip function which takes one thing from each list. Here I illustrate just using the days just to type less.

ordered_list = [5, 12, 19, 27, 3]

start_dates = ordered_list[:-1] # [5, 12, 19, 27]

end_dates = ordered_list[1:] # [12, 19, 27, 3]

zip(start_dates, end_dates) # [(5, 12), (12, 19), (19, 27), (27, 3)]Putting this all together:

sql = """SELECT start_datetime

FROM moon_phases

ORDER BY start_datetime ASC"""

cursor.execute(sql)

results = cursor.fetchall() # list of dicts

# make into a simple list of datetimes

just_datetimes = []

for row in results:

just_datetimes.append(row['start_datetime'])

update_sql = """UPDATE moon_phases

SET end_datetime = %(end_datetime)s

WHERE start_datetime = %(start_datetime)s

"""

start_dates = just_datetimes[:-1]

end_dates = just_datetimes[1:]

for start_date, end_date in zip(start_dates, end_dates):

# subtract 1 second from end_date to avoid overlap

end_date = end_date - datetime.timedelta(seconds=1)

param_dict = {"start_datetime": start_date,

"end_datetime": end_date}

cursor.execute(update_sql, param_dict)Note that this leaves the final period without an end_datetime. That is unavoidable because that data is not in the database.

The correlated sub-query solution is better in that respect because it would put events in the last period.

Interacting with the database from python

Reading many rows from database without bringing them into memory

cursor.fetchall() is useful but returns all the results into memory in Python. Avoid this with large queries as you might hit errors like pymysql.err.OperationalError: (2013, 'Lost connection to MySQL server during query. Instead you can use cursor directly as an iterator.

sql = "SELECT * FROM venues" # SQL queries are just a string.

cursor.execute(sql)

#results = cursor.fetchall() don't include this line

csv_column_order = ['id','name','capacity'] # manually

# csv_column_order = [i[0] for i in cursor.description] # automatically

with open('exported-venues.csv', 'w') as csvfile:

myCsvWriter = csv.DictWriter(csvfile, fieldnames = csv_column_order)

myCsvWriter.writeheader()

for row in cursor: # rather than 'for row in results'

myCsvWriter.writerow(row)Get columns names in order while using DictReader

DictReader is convenient but we lose the order of the columns as returned by the database server. The cursor has this information, but it is a little hidden. You can get them in a list (thus preserving order) using this code:

column_names = [i[0] for i in cursor.description]Insert multiple rows into the database based on values in different columns in a single row (aka pivot longer)

Use an inner for loop over the columns within a row. e.g., a CSV about Gold Medals

country,1984,1988,1992

Australia,32,33,34

USA,60,23,34for row in myCSVReader:

country = row["country"] # some item that applies to all.

for key,value in row.items(): # row is a dict : { "1984": 32, "1988"}

if (key == "country"):

continue # skip this item.

param_dict = { "country": country,

"year": key,

"gold_medals": value}

cursor.execute(sql_insert,param_dict)Afterwards these data would be represented in a “long” format:

id, country, year, gold_medals

1, Australia, 1984, 32

2, Australia, 1988, 33

3, Australia, 1992, 34

4, USA, 1984, 60

5, USA, 1988, 23

6, USA, 1992, 34See Data Transforms and the School Absences homework (which is similar, except iterating over a string in the row rather than the row items).

Handle names with different forms

In the database, create an entity for the thing and an entity for the names. e.g., Person has_many PersonName, PersonName belongs_to Person. or Country has_many CountryName, CountryName belongs_to Country. Use that data to create a dictionary that enables quick conversion from any form of the name to either a standard name or the person/country id.

us_names = ["usa","United States of America", "US"]

countryMap = { "usa": "usa",

"United States of America": "usa",

"US": "usa" }

for alt_name in us_names:

print("Even given {}".format(alt_name))

#map alt_name to "usa" by using it as a key to the dictionary

print("We can get {}".format(countryMap[alt_name]))See code and database schema at Miscellaneous Tips

Handle state names and abbreviations

State names and abbreviations are examples of different forms of names. See above for general approach, but for US states specifically there is really useful data available. This used to be on a website called statetable but I’ve cached a copy here from data.world: https://data.world/markmarkoh/us-state-table

| id | name | abbreviation | fips_state | assoc_press | standard_federal_region | census_region | census_region_name | census_division | census_division_name | circuit_court |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alabama | AL | 1 | Ala. | IV | 3 | South | 6 | East South Central | 11 |

| 2 | Alaska | AK | 2 | Alaska | X | 4 | West | 9 | Pacific | 9 |

| 3 | Arizona | AZ | 4 | Ariz. | IX | 4 | West | 8 | Mountain | 9 |

This includes abbreviations and useful stuff like which region of the country a state is in, which allows you to do you analyses via region which can be easier to understand that by state.

Avoid inserting duplicate records

Use three sql queries: a SELECT an UPDATE and an INSERT. SELECT to see if a record already exists, if it does then an UPDATE (or nothing), if it doesn’t then a SELECT.

sql_select = "SELECT id from venues WHERE name = %(venue_name)s"

sql_update = "UPDATE venues SET capacity = %(capacity)s WHERE id = %(found_id)s"

sql_insert = """ INSERT INTO venues(name,capacity)

VALUE (%(venue_name)s,%(capacity)s)

RETURNING id"""

param_dict = { "name": "AMD",

"capacity": 2000 }

cursor.execute(sql_select,param_dict)

if (cursor.rowcount == 0): # none found by SELECT

cursor.execute(sql_insert,param_dict)

venue_id = cursor.fetchone()['id'] # from INSERT ... RETURNING id

else:

venue_id = cursor.fetchone()['id'] # from select

# update if additional fields are being added.

param_dict["id"] = venue_id

cursor.execute(sql_update,param_dict)See also class notes on (CSV to SQL via Python)[http://howisonlab.github.io/datawrangling/class_modules/12_csv_to_sql_via_python/#find-or-create-an-id-csv-contains-mix-of-data-about-new-and-existing-entities]

Lookup foreign keys while inserting data

tl;dw Use the “find or create” sequence.

Ultimately we want to insert into the performances table, but to do that we need the band_id and the venue_id. However, we don’t yet have those. Instead we have the venue_name and the band_name. So we have to convert those to ids. We convert those by first checking if they are already in the database (using a SELECT). If they are, then we have the id. If they aren’t then we use an INSERT to create the row, and get the id that way. Either way, we end up with the id we need and can use those in the insert into performances.

sql_insert_performance = """INSERT INTO performances(start,band_id,venue_id)

VALUE (%(band_id)s, %(venue_id)s, %(start_time)s)"""

sql_select_venue = "SELECT id from venues WHERE name = %(venue_name)s"

sql_select_band_name = "SELECT id from bands WHERE name = %(band_name)s"

sql_insert_venue = "INSERT INTO venues(name) VALUE (%(venue_name)s"

sql_insert_band_name = "INSERT INTO bands(name) VALUE (%(band_name)s"

# data normally would come from a CSV

incoming_data = [ { "band_name": "Cut Copy",

"venue_name": "AMD",

"start_time": "2016-03-12 18:00:00"} ]

for row in incoming_data:

# find or create venue

cursor.execute(sql_select_venue, row)

results = cursor.fetchall()

if (len(results) == 0):

cursor.execute(sql_insert_venue, row)

venue_id = cursor.lastrowid # get id of newly created venue.

else:

venue_id = results[0]["id"] # get found id.

# find or create band

cursor.execute(sql_select_band, row)

results = cursor.fetchall()

if (len(results) == 0):

cursor.execute(sql_insert_band, row)

band_id = cursor.lastrowid # get id of newly created venue.

else:

band_id = results[0]["id"] # get found id.

# add ids to param_dict

param_dict = {"band_id" = band_id,

"venue_id" = venue_id,

"start_time" = row["start_time"]}

cursor.execute(sql_insert_performance, param_dict)You might think it worthwhile to create a reuseable find_or_create function, but it is very tricky to do that in general, it is almost worthwhile to do a find_or_create function for each table if you always do lookups by a specific column. Honestly, though, by the time that is worthwhile you should consider using an Object-Relational Mapping library, such as SQLAlchemy.

See CSV to SQL via Python materials.

Join database tables without foreign keys

Foreign keys are a convenience but not required for joining tables, any field with matching values will work. e.g.,

-- state_gdp(state_abbr,gdp)

-- state_weather(state_abbr,weather)

SELECT *

FROM state_gdp, state_weather

WHERE state_gdp.state_abbr = state_weather.state_abbror

-- addresses(id,business_name,address,zip)

-- incomes(id,zip,avg_income)

SELECT *

FROM addresses, incomes

WHERE addresses.zip = incomes.zip

-- Now count the businesses in each zip and the income

SELECT zip, COUNT(*) as num_businesses_in_zip, avg_income as avg_income_in_zip

FROM addresses, incomes

WHERE addresses.zip = incomes.zip

GROUP BY zipSo you don’t need to create primary key/foreign key relationships although they are very useful and required if there are related objects with no field to match by.

Speed up mysql queries-avoiding Lost connection to MySQL server during query error

Ensure you have defined indexes on the columns you use in your joins. The server has a guard to ensure that queries don’t block up the server for others. That guard kills long-running queries. Indexes make it much easier for mysql to do the joins. You can define these through phpmyadmin using the Index icon to the right of the column row on the structure tab (it might be hidden under the “More” button if you don’t have enough wide on your screen).

You can tell if your indexes are being used by adding EXPLAIN to the front of your query (check the possible_key and key output, you want to see something there). See more here: https://www.sitepoint.com/using-explain-to-write-better-mysql-queries/ and http://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/5.7/en/using-explain.html

So why not just add indexes to everything? They take up space and have to be updated for each insert so there are many trade offs.

Speed up mysql inserts

Help, it takes ages for my data to insert! See Importing large files

First try is turning off autocommit:

# Before first execute.

cursor.execute("SET autocommit = 0")

for row in myCSVReader:

cursor.execute(sql, row)

#All execute done.

cursor.execute("COMMIT")Second try, for very large files, is using python to create a csv that exactly matches the database table (name of file and names of headers) and mysqlimport from the terminal (not via python). This will ask for your mysql password before doing the insert.

mysqlimport -u testuser -p --local --fields-terminated-by=',' \

--fields-enclosed-by='"' --ignore-lines=1 \

testuser_empty_music_festival ./tickets.csv btw, don’t even think about using phpmyadmin for this, the web interface does not work with uploading large files.

Addresses and GIS

Get the distance between two addresses

This requires using external libraries, either Maps or GIS. I show an example using Open Street Map. See files below (documentation in the .py file)

Analysis

Complex analyses are beyond the scope of this course, but here are just a few simple things that might be useful.

Assess correlation between two variables

The SciPy and Numpy modules offer many stats functions. Here’s correlation, you need to provide two lists of equal length to compare. These will likely be columns from your database query. https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy-0.14.0/reference/generated/scipy.stats.pearsonr.html

import scipy.stats

# extract two columns from your query.

crimes = []

gdp = []

for row in results:

crimes.append(row["crime"])

gdp.append(row["gdp"])

# pearsonr and spearmanr return correlation and confidence interval. Get just the correlation using [0]

# pearsonr uses magnitude

print(scipy.stats.pearsonr(crimes,gdp)[0])

# spearmanr uses just rank

print(scipy.stats.spearmanr(crimes,gdp)[0])Note that easier access to columns etc can be obtained through the pandas module, but that’s beyond the scope of this course.

── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.5

✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.1

✔ ggplot2 3.5.2 ✔ tibble 3.3.0

✔ lubridate 1.9.4 ✔ tidyr 1.3.1

✔ purrr 1.1.0

── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errorsRead colors from Excel files

Colored backgrounds are often used in Excel manual data entry to indicate things like status. They are tricky because they are not passed to textual formats like csv. It is even tricky for Excel itself to turn the color metadata about a cell into data in cells (it requires formula that not all versions of Excel have, or an older scripting language called VBA).

We can, though, get this done in both R and Python. For SQL based workflows we would need to look beyond SQL; so the R and Python based solutions would probably be used within a dbt or other ETL pipeline.

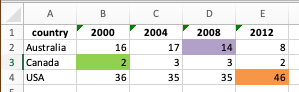

Here is an example Excel file with coloring applied. We will read this, convert to a long format, and add a column showing the color of the cell.

library(writexl)

library(GmooG)

data(OlympicPerfs)

reduced_data <- OlympicPerfs |>

filter(medalType == "GOLD") |>

group_by(games, country, medalType) |>

summarize(medal_count = n()) |>

ungroup() |>

filter(country %in% c("Australia", "United States of America", "Canada"),

games |> str_detect("2000|2004|2008|2012")) |>

separate_wider_delim(games, delim = "-", names = c("host", "year")) |>

select(!c(medalType, host)) |>

mutate(country = case_match(country,

"United States of America" ~ "USA",

.default = country),

year = as.numeric(year)) |>

pivot_wider(names_from = year, values_from = medal_count) |>

select(country, `2000`, `2004`, `2008`, `2012`) `summarise()` has grouped output by 'games', 'country'. You can override using

the `.groups` argument.# #| eval: false

#

# library(openxlsx)

# library(dplyr)

#

#

# file_path = "faq_assets/olympic_excel_to_color.xlsx"

# sheet = 1

#

# read_excel_with_colors <- function(file_path, sheet = 1) {

# # Load workbook

# wb <- loadWorkbook(file_path)

#

# # Read the data

# data <- read.xlsx(file_path, sheet = sheet)

#

# # Create a matrix to store colors

# colors <- matrix(NA,

# nrow = nrow(data),

# ncol = ncol(data),

# dimnames = list(NULL, names(data)))

#

# # Get sheet index

# if(is.numeric(sheet)) {

# sheet_idx <- sheet

# } else {

# sheet_idx <- match(sheet, names(wb))

# }

#

# # Get fill colors for each cell

# for(row in 1:nrow(data)) {

# for(col in 1:ncol(data)) {

# style <- wb$worksheets[[sheet_idx]]$sheet_data$cellStyles[row + 1, col]

# if(!is.null(style)) {

# fill <- style$fill

# if(!is.null(fill)) {

# colors[row, col] <- fill

# }

# }

# }

# }

#

# # Convert colors matrix to data frame

# colors_df <- as.data.frame(colors)

# names(colors_df) <- names(data)

#

# # Return both data and colors

# return(list(

# data = data,

# colors = colors_df

# ))

# }

# Example usage:

# First ensure you have both required packages:

# install.packages(c("xlsx", "rJava"))

#

# Then use the function:

# result <- read_excel_with_colors("your_file.xlsx")

#

# View results:

# head(result$data)

# head(result$colors)

# Example usage:

# First install the xlsx package if you haven't:

# install.packages("xlsx")

#

# Then use the function:

# result <- read_excel_with_colors("your_file.xlsx")

#

# View results:

# head(result$data)

# head(result$colors)

# Test the function with a small example:

# file_path <- "test.xlsx"

# result <- read_excel_with_colors(file_path)

#

# # View the first few rows of both data frames

# head(result$data)

# head(result$colors)

# Example usage:

# file_path <- "your_excel_file.xlsx"

# result <- read_excel_with_colors(file_path)

#

# # Look at the data

# print(head(result$data))

#

# # Look at the colors

# print(head(result$colors))

#

# # To see which cells have a specific color (e.g., red FF0000)

# color_mask <- result$colors == "FF0000"

# colored_cells <- result$data[color_mask]

# Example usage:

# file_path <- "your_excel_file.xlsx"

# result <- read_excel_with_colors(file_path)

#

# # View the data

# head(result$data)

#

# # View the colors

# head(result$colors)

#

# # Combine data with colors for a specific column

# data_with_colors <- cbind(

# result$data,

# color = result$colors[, 1] # Replace 1 with your column number

# )# df <- read_excel_with_colors("faq_assets/olympic_excel_to_color.xlsx")

# Example usage:

# file_path <- "your_excel_file.xlsx"

# result <- read_excel_with_colors(file_path)

#

# # Access the data

# data <- result$data

#

# # Access the colors

# colors <- result$colors

#

# # Combine data with colors for a specific column

# combined <- data %>%

# mutate(column_colors = colors$column_name)

#

# # Filter rows based on color

# red_rows <- data[colors$column_name == "FF0000", ]Read multiple files with similar formats, getting data from file names

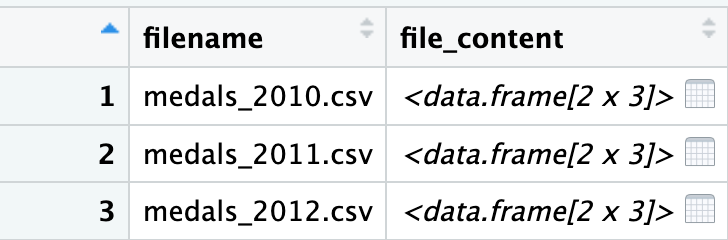

Quite often we have data split up across multiple files. For example we might have these files:

medals_2010.csv

medals_2011.csv

medals_2012.csvbut each have the same format inside, e.g.,

event,medal,countryNotice that the filename has data in it, each file has the year. So eventually we would like to have

year,event,medal,countryWe can accomplish this within a dataframe by using an apply (called map in Tidyverse) and an unnest. We use these steps:

- We start with a dataframe with a column that contains the filenames and the years

- We use each row as parameters to a function (this is very much like iterating over the rows in the table); here the function reads the whole csv into a single cell. This move is can be called

applybut in Tidyverse it is calledmap. - We

unnestthe cell containing the CSV, which places each row in the nested CSV alongside copies of theyearcolumn. This is like unnesting a list of comma separated course names, but instead of a single item, the nested items are rows.

# first write out the files

tribble(

~event,~medal,~country,

"100m", "gold", "Bahamas",

"100m", "silver", "Jamacia"

) |> write_csv('medals_2010.csv')

tribble(

~event,~medal,~country,

"100m", "gold", "USA",

"100m", "silver", "Dominica"

) |> write_csv('medals_2011.csv')

tribble(

~event,~medal,~country,

"100m", "gold", "Bahamas",

"100m", "silver", "USA"

) |> write_csv('medals_2012.csv')Now that we have the files we will start with the filenames in a dataframe.

names_and_filecontent <- tribble(~filename,

"medals_2010.csv",

"medals_2011.csv",

"medals_2012.csv"

) |>

mutate(file_content = map(filename, read_csv, show_col_types = FALSE))

names_and_filecontentWe now have a new column file_content; this has the type list and the items within it are tbl_df which means they are dataframes. If we double click or use View() in Rstudio we can see a little more clearly:

If we double click one of the cells on the right, we zoom in and see the full csv contained within:

Now we can use unnest to bring these all out to a familiar dataframe.

names_and_filecontent |>

unnest(cols = file_content)So the filename column is repeated for each of the rows that used to be in the file_content column, which means that we know the origin of each row. We can now get our year from our filename using an extract and a regex that matches “the actual characters 2 and 0, followed by any two characters, followed by .csv

names_and_filecontent |>

unnest(cols = file_content) |>

mutate(year = str_extract(filename, "20\\d\\d")) |>

select(year, event, medal, country)Vizualize correlations between three variables

Imagine a project where you have three variables, for example:country_population, country_gdp, and country_latitude (distance from equator).

It’s straightforward to visualize correlation between any two of these: you can use a scatterplot with the vertical axis being one variable, and the horizontal axis being a second variable. But how can you get the third variable represented there as well?

You can use the values in the third variable to change the dots in some way, changing their color or their size is the usual approach. You can then experiment with different combinations, such as population and gpp on the axis, or latitude shown by color, or swap the latitude onto the vertical axis and use the size of a point to show the population.

There are good examples in R tidyverse and Python here https://sscc.wisc.edu/sscc/pubs/DWE/book/3-4-sect-ggplot-multiple-var.html

Quarto tips

Ensuring images are not missing from html exports

html usually has images just in an <img> tag which points to separate image files.

But when you want to create just a single file that you can submit to the assignment you can’t provide the image files separately.

One approach to this is that the image files get “base64 encoded” as text within the HTML file.

Use this in the YAML header for the quarto file:

```{yaml}

format:

html:

embed-resources: true

# self-contained: true <-- older but same result

```See more quarto html export tips at the quarto documentation.

Tabsets

Since we are working across four frameworks it can be convenient to be able to show four versions of the same data operation. In quarto we can do this with tabsets (just as we’ve done on this page). The documentation on how to do this is at https://quarto.org/docs/output-formats/html-basics.html#tabsets

Why don’t you teach …

What is a list comprehension and why is it not taught

Python offers a syntax to simplify a common idiom:

# Pull all "some_key" out of the list of dicts

new_list = []

for item_dict in myListOfDicts:

value_for_key = item_dict["some_key"]

new_list.append(value_for_key)Could be written as:

new_list = [ item_dict["some_key"] for item_dict in myListOfDicts ]That’s called a List Comprehension, see more here http://www.pythonforbeginners.com/basics/list-comprehensions-in-python. I don’t teach it in the course because a) I grew up on other languages, and b) I find it confusing to follow the step by step logic. Anyway, it’s a useful thing to know about.

Why don’t you teach the JOIN keyword (aka ANSI JOINs, aka explicit joins)

In the course we learn joins that look like this:

SELECT *

FROM person, tickets

WHERE person.id = tickets.person_idAnother way of writing that is:

SELECT *

FROM person JOIN tickets

ON person.id = tickets.person_idThe first way is variously called “implicit join”, “old-style join” and the second way is variously called “explicit join”, “ANSI style join”. You may even here the first way called “the awful, broken, don’t ever do it way” or the “wrong way” and the new style the “right way”. See http://www.sqlservercentral.com/blogs/brian_kelley/2009/09/30/the-old-inner-join-syntax-vs-the-new-inner-join-syntax/

I teach the “old-style” or “implicit” notation because I explain joins as a logical extension to filtering data using the WHERE clause: joins, regardless of syntax, can be conceptually understood as row-by-row filters on a cross-product (regardless of whether they are implemented that way).

The downsides are well known:

- The server gets slammed by cross-products without joining expressions in the

WHEREclause, - Unexpected rows when using

ORin combination with “implicit” joins. See My query using OR is returning unexpected rows - Difficult extension to other types of joins, particularly