---

config:

gitGraph:

parallelCommits: true

mainBranchOrder: 1

---

gitGraph

commit

commit

commit type: HIGHLIGHT

branch pie_chart_branch order: 0

commit

commit

checkout main

commit

branch new_database order: 2

commit

commit

checkout main

merge new_database

commit

checkout pie_chart_branch

commit

commit

commit

checkout main

merge pie_chart_branch

22 Rebase for synchronizing work

Thanks for your contribution; could you rebase this against main? Thanks!

That is also a common request from maintainers, and one that can cause confusion for new contributors.

When one is working on a problem, others may be working in parallel. And their parallel work may be finished before one’s own work is. Thus the starting point for one person’s work (branching point) can “go stale” making it harder to integrate.

While git merge and resolving syntax level conflicts can resolve some of this, it is often easier to understand and review work if it is presented as changes against an updated starting point.

As a concrete example imagine a project to build a dashboard.

Imagine that you fork the repo in January to implement a new type of visualization (let’s say a pie chart). You work on this during January and February, finally nailing it down at the start of March. Meanwhile, though, others in the project have spent February introducing a whole new way of accessing databases.

By the time you make a pull request at the start of March things have changed a lot since you branched in January.

--January-|------February--------------|--March

__pie_chart_branch___________

/ \

main--|--|-----------------------|----|-------

\ /

\__new_database_____/If you submit a PR without updating, the maintainers will likely ask you to update your branch to make it work with the new database system.

First thing to do is to update your local repository with the changes from upstream.

git pull upstream mainThen you could try two options:

- Either merge

mainintopie_chart_branchyourself (this is what we did in earlier exercises) - Rebase

pie_chart_branchon main

Option 1 is possible, but often merging your work involves touching parts of the system you don’t know much about, and it is better left to the core developers. In addition, merging in this way leaves merge commit messages and some projects really don’t like those because they make the history harder to read. It also leaves all of your “intermediate” commits in the history (things like “fix typo” and “forgot comma”). Some find that too much information.

Option 2 is generally preferred, since it focuses on clear communication via PRs that are easier to read and review. Often this just means a single commit showing the differences between the most updated work and the work that you want to contribute. For those viewing the history, it will be just the same as if pie_chart_branch was created in late February and you did all the work very quickly!

Option 2 is called rebase. We specify a new starting point, and git gives us a little UI in which we can choose which commits to include, which to “squash”, and we can even reorder commits.

We have an example set up. First we will clone it, change directory into the repo, and then switch to the pie_chart_branch.

cd ~

git clone https://github.com/jameshowison/320d_rebase_example.git

cd 320d_rebase_example

git checkout pie_chart_branchOur git viz command (See Section B.3 to set up) shows us the situation:

$ git viz

* 2b6a2cf (origin/main, origin/HEAD, main) database 2

* 70c14e7 database 1

| * 246e49e (HEAD -> pie_chart_branch, origin/pie_chart_branch) pie chart 3

| * 4c12962 pie chart 2

| * 123593a pie chart 1

|/

* ccd6067 second commit

* 512525e first commit

* 20b7fb5 Initial commitWe have two branches (main and pie_chart_branch). pie_chart_branch branched off from main at “second commit”, and since then more work has been added to main (the database related commits). We also have three separate commits for pie_chart_branch.

So, in a prettier diagram, the situation looks like this:

---

config:

gitGraph:

parallelCommits: true

---

gitGraph

commit

commit

commit type: HIGHLIGHT

branch pie_chart_branch

commit

commit

checkout main

commit

commit

checkout pie_chart_branch

commit

We don’t want to just merge main into our branch, and then merge the result back into main. This would produce a relatively complex history that can be confusing to interpret:

---

config:

gitGraph:

parallelCommits: true

---

gitGraph

commit

commit

commit type: HIGHLIGHT

branch pie_chart_branch

commit

commit

checkout main

commit

commit

checkout pie_chart_branch

commit

merge main

checkout main

merge pie_chart_branch

Instead, we want it to look as though pie_chart_branch came off the tip of main, like this:

---

config:

gitGraph:

parallelCommits: true

---

gitGraph

commit

commit

commit type: HIGHLIGHT

commit

commit

branch pie_chart_branch

commit

commit

commit

To accomplish this we can use a git command called rebase. We say that we will “rebase” the pie_chart_branch against main.

git checkout pie_chart_branch

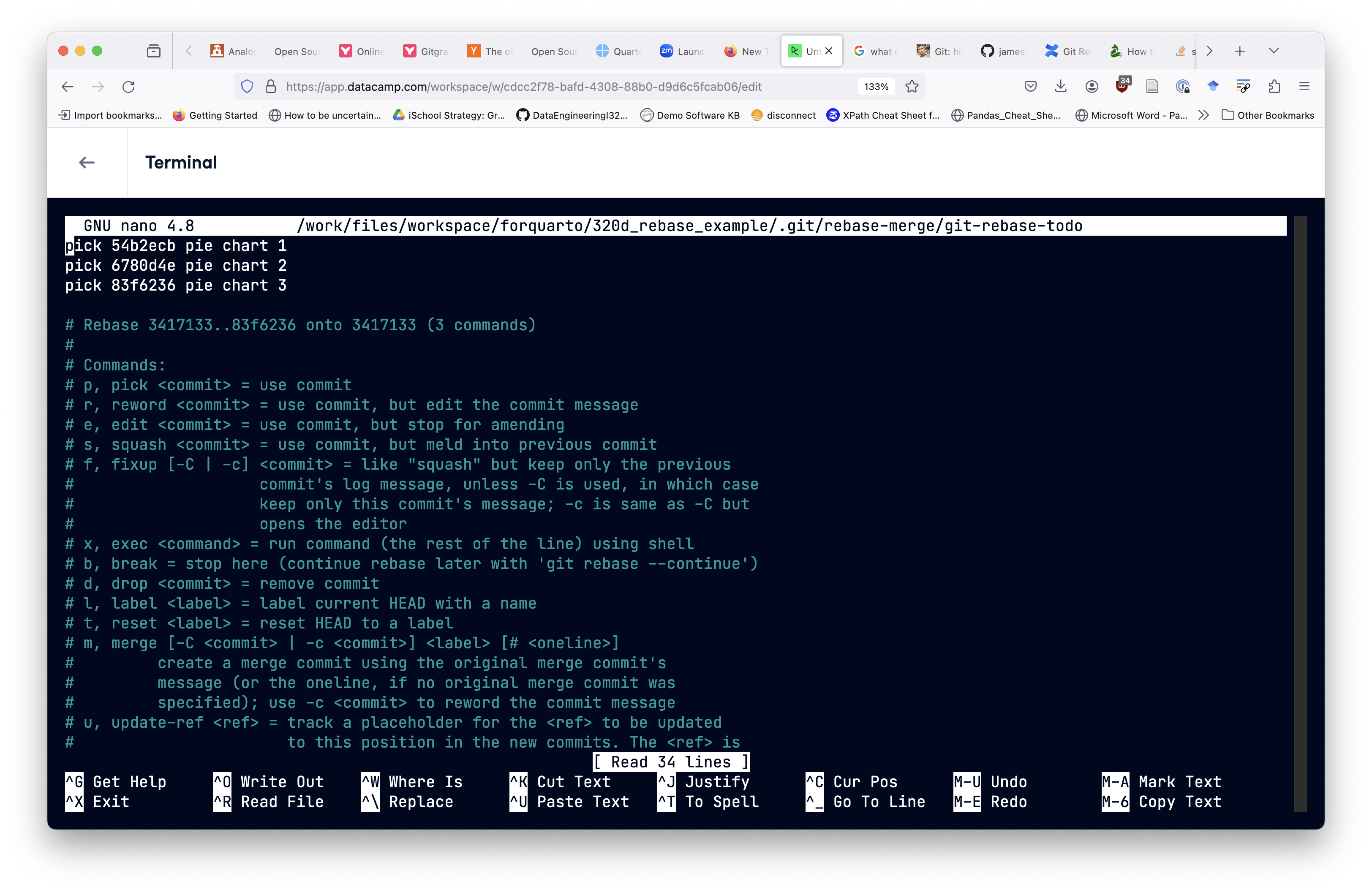

git rebase -i mainThis puts us into a textual UI, with guidance at the bottom. We can use the arrow keys to move around. In this UI we are editing a text file (so we are using the Nano editor). To begin, understand that git rebase first changes the pointer to pie_chart_branch to point at the commit we specified. It then finds the point at which pie_chart_branch diverged from the specified commit’s history. Each line is a command, the lines are instructions and are executed in order. In the following case, this is as if we checked out main, and then sequentially called git cherry-pick on the commits in pie_chart_branch.

We use Ctrl + O to save (aka “write-Out”) and Ctrl+X to exit the editor. We should see a count of commits being rebased and then a message about a successful rebase. Using git viz will then show us:

* 16fa532 (HEAD -> pie_chart_branch) pie chart 3

* bf585ba pie chart 2

* a2591db pie chart 1

* 3417133 (origin/main, origin/HEAD, main) database 2

* 32c1b1c database 1

| * 83f6236 (origin/pie_chart_branch) pie chart 3

| * 6780d4e pie chart 2

| * 54b2ecb pie chart 1

|/

* 52bd3fd second commit

* 0aefb6a first commit

* 9ad07d3 Initial commitThis is a little hard to read. This is because the origin/ branches are showing (and those are up on the GitHub server and not yet changed). Look closely at the pie_chart_branch and down the left column. We now see that pie chart 1 commit comes directly after the two commits on main, just as though the work started there.

To get this to also be reflected on the server we would have to do a “force push” git push -f which makes the server reflect the local repo. Note that this is usual for rebase on branches, but one should be very hesitant with any force operations on main or a branch shared with others. (Since you are not the owners of the repo, you won’t be able to do a force push here). After the force push, things are neater:

* 16fa532 (HEAD -> pie_chart_branch, origin/pie_chart_branch) pie chart 3

* bf585ba pie chart 2

* a2591db pie chart 1

* 3417133 (origin/main, origin/HEAD, main) database 2

* 32c1b1c database 1

* 52bd3fd second commit

* 0aefb6a first commit

* 9ad07d3 Initial commitYou might be thinking, didn’t we do pretty much the same thing with cherrypick? And yes, in this situation rebase is very similar to cherrypick.

Rebase does offer some additional opportunities though. Notice that the textual UI shows more options than just ‘pick’. One option is ‘squash’ which takes changes from multiple commits and presents them in a single commit. This can make a git history easier for teammates to understand.

22.1 Commits vs. Patches

If you think about it, what we’ve just done is magic from our current understanding of how Git works. If commits are whole-filesystem snapshots (which they are!), then why would rebasing our commits change their contents? There’s a new concept lurking here that also explains the behavior of git cherry-pick: “patches”.

In Git, a patch represents the difference between two commits. Patches consist of three sets of instructions:

- Files to be added.

- Files to be modified.

- Files to be removed.

Modifying files is an interesting case: Git considers the state of the file both before and after the patch. It’s complicated, but generally a patch can only automatically be applied to a file if the file looks “enough” like the file the patch was made for. For instance, if a patch is told to a remove a particular line and the line no longer exists, this may result in a merge conflict.

When we modify history, what Git does is calculate “patches” between commits, and then tries to calculate the state of the repository as if that sequence of patches had been applied in order to generate the new commits. When we git rebase, we’re telling Git that we want it to calculate what the state of commits on our current branch would be if we had applied the patches we’re rebasing on first. This is essentially the inverse of git merge, which tries to calculate what happens if we apply the changes from the target branch after the changes we’ve already made.

You can think of git diff as calculating the “patch” between two commits.

If you write the output of git diff to a file, e.g. git diff main my-branch > my-branch.patch, you get a valid “patch file” that you can git apply. Fortunately, we don’t need these since we’ve long passed the days of needing to literally email changes.

When we get “merge conflicts” - be they via git merge, git cherrypick, or git rebase, it means that for some reason Git wasn’t able to apply the patch representing the difference between two commits. For instance, if you added a file to main, and separately also added that file to pie_chart_branch, then all of these commands will flag the file as a potential merge conflict.

22.2 Adding squash

We want to squash those three commits down to one commit, and (like before) we want that commit to represent changes as though we had branched off main after the database 2 commit. First, remove the directory we have been working in and reset things with a new clone.

cd ..

rm -rf 320d_rebase_example

git clone https://github.com/jameshowison/320d_rebase_example.git

cd 320d_rebase_example

git checkout pie_chart_branchJust as before we use:

git rebase -i mainThis puts us back into a textual UI, with guidance at the bottom. This time instead of leaving all three as ‘pick’ we change two of them to squash. We do this by editing the file so that two of the lines show s instead of pick.

After we use Ctrl + O to save (aka “write-Out”) and Ctrl+X to exit the editor, git completes the squash by including all the changes in a single commit. We are then returned to the editor to create a new commit message.

Finally, we can use git viz to see the new situation.

* 32f895e (HEAD -> pie_chart_branch) Here I have tidied up the history to make it easier to read. Pie chart draws pies.

* 2b6a2cf (origin/main, origin/HEAD, main) database 2

* 70c14e7 database 1

| * 246e49e (origin/pie_chart_branch) pie chart 3

| * 4c12962 pie chart 2

| * 123593a pie chart 1

|/

* ccd6067 second commit

* 512525e first commit

* 20b7fb5 Initial commitIgnore the remote branch (origin/pie_chart_branch), and focus only on the local branch (HEAD -> pie_chart_branch). Instead of all three commits, we now only see a single commit (c367b8a).

Note that in these examples we did not encounter any conflicts (because edits were all on different files). In reality, though, when commits are moved around, rebased, and squashed, sometimes those operations result in conflicts (just as happens with merge). In that case git add the conflict symbols (<<<<<< and ========== and >>>>>>>>>) which all need to be removed, then the files added and finally we run git rebase --continue. Git does provide useful messages through that process with guidance on the likely next steps.

None of the actions we’ve discussed today actually delete any commits from the repository. You can still git checkout the commit IDs from before rebasing and/or squashing, and even see their relationships to the work tree with git viz --reflog. This is both a good thing (you can easily undo these actions) and a bad thing (removing problematic commits is hard).

22.3 Rebase Exercise

In groups of three, a Maintainer and two contributors (Contributor A and Contributor B), begin by setting up the collaboration network (a new repo on GitHub, forks, clones and setting upstream). Then work together to implement these steps:

- Maintainer makes two commits to the main branch. Contributors use

git pull upstream mainto synchronize. - Each contributor creates a feature branch, and adds two commits to a file named “[yourname].txt” where “yourname” is replaced with your name.

- Contributors create PRs that Maintainer sees on the upstream/shared repository. Do not continue until both contributors have created their PRs.

- Maintainer asks Contributor A to squash their contribution.

- Contributor A uses rebase and squash, then

git push -fto get their PR synchronized with their rebase. - Maintainer accepts Contributor A’s PR, merging to main.

- Maintainer asks Contributor B to rebase and squash their contribution.

- Contributor B does a

git pull upstream mainto get the new work onto the main branch in their local git. - Contributor B uses rebase and squash (as above), then

git push -fto get their PR synchronized with their rebase. - Maintainer should then check the PR. They will find only a single commit (the two previous ones squashed together), now looking as though it branched off main after the first contributor’s work. Maintainer can then accept the rebased PR.

- Both contributors should synchronize (

git pull upstream mainand then git push to sync their forks.)